Twitter | Youtube | Linkedin | Instagram

Sports science is making its way to the masses. Technology is becoming more accessible and affordable, sport science jobs are spawning by the day, and coaches are accepting that there are insights technology can give them to help them and their athletes become better.

But just like anything else in the world of sports performance, whether it be working with new athletes, trying a new training method, etc., there’s a learning curve.

Not to say that I’m an expert, but I’ve definitely had my own learning curve in this relatively new field.

Guide

My Journey in Sports Science

I spent two years as a “Sports Scientist” during my graduate assistantship at TCU. This included two years of remote sport science-ing for the same team post-graduation and getting my thesis published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research.

On top of that, as a full-time sports performance and speed development coach, I was also the “Sport Science Coordinator” at a training facility called TCBoost Sports Performance.

At TCBoost, I helped organize and put together all of our training technologies. This involved connecting it back to coaching better and making better decisions.

Reflecting back on those two experiences, there’s one big lesson, the foundation of sports science, that I feel most practitioners miss nowadays: it all starts with a plan.

The Importance of Planning in Sports Science

Think about it: coaches write out lifting programs, practice plans for the week, and testing days around tapers, assuming that’s when athletes will perform their best. This concept shouldn’t be too foreign.

But when was the last time you wrote out how the data from your sport science technology should be?

And herein lies what sports science is: applying science to improve at sport.

The scientific method: a question or a hypothesis, collect data and figure out what it means.

Essentially, the plan I’m referencing is another way to say hypothesis.

Retrospective Analysis in Sports Science

Most of the time, sports science is retrospective. It looks back at the previous day or week of training and seeing how it went.

The bar speed of a squat was 0.56 m/s, the team average was 7,301 yards covered, and the athlete’s soreness was 6 out of 7, which is higher than the 5 of the previous day.

Those data points already happened, so what insights can that give us?

On their own, not much.

Consequently, looking at how the data turned out in the past is only valuable if you have a plan of what it should’ve been.

If we guessed/predicted that the bar speed of a squat at a certain weight should’ve been 0.50 m/s, then the athlete was feeling pretty good. If the practice plan was to have a medium-load day which is 5,000-6,000 yards, then the coaches went too hard and the athletes accumulated more fatigue than planned. If the prior day’s training was an “active recovery” day, then an increase in soreness should spur some conversations with the coaching and support staff.

Proactive Planning: A Real-Life Example

See how in those examples the plan of what should’ve happened gave so much more context and helped drive potential action?

Hopefully, this is not a ground-breaking idea that you should have a plan and rhyme and reason for what you’re doing.

But proactively, even if you know in your head, write out and predict how your sports science data should go.

Here’s a really good real-life example.

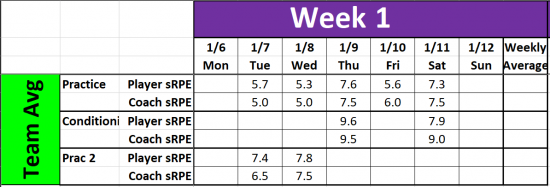

Doing sports science for TCU Beach Volleyball, I had the assistant coach give each practice plan a programmed/anticipated sRPE (session-rating of perceived exertion, 1 out of 10 how hard was the athlete’s effort). I then compared that to the player’s responses post-practice.

After a semester, the coach had a 0.77 correlation with the player’s responses, meaning she was accurate enough to predict how hard the practices would be for the athletes.

That meant that we could proactively plan the training intensities of the week ahead of time instead of working backwards after the week was done.

Conclusion

This can be as simple or detailed as you want it to be, assigning something a “low, medium, or high,” giving it a number 1 to 10 like a sRPE, or very detailed like how many yards covered each section of a practice should have.

Moral of the story: you have a hypothesis whether you know it or not. Usually, it’s just masked as coaching intuition, but you can do some really cool things when the plan before is just as objective as the data after.

Our Collaborative Planning Process allows you to prepare your project stress free by allowing our team to become your personal project manager. The real-time planning and organization of thoughts gives you back time and clarity as a leader. If you’d like to schedule a FREE CONSULTATION, please fill out this form.

Matt Tometz

Assistant Director of Olympic Sports Performance, Baseball and Swimming | Northwestern University

Additional articles written Click HERE

Matt Tometz specializes in integrating coaching and data with a focus on speed development. He emphasizes that his views are his own.

Currently, he is the Assistant Director of Olympic Sports Performance for Baseball and Swimming at Northwestern University. Previously, he served as a Sports Performance Coach and Sport Science Coordinator at TCBoost Sports Performance in Northbrook, IL, and as a Sport Scientist for Texas Christian University Women’s Beach Volleyball.

His research, “Validation of Internal and External Load Metrics in NCAA D1 Women’s Beach Volleyball,” has been published in The Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. An ex-student-athlete at Truman State University, he brings a wealth of experience and knowledge to the field.

Email: matthew.tometz@gmail.com